Fighting an alien war

Four recent books honour the memory of the Indian soldiers who fought on the British empire's side in the world wars

Premium

Premium

The number of Indians who enlisted and fought to protect the British empire during the two world wars was nearly four million and, of them, close to 160,000 died in the battlefield or from wounds suffered during conflict. That generation is now fading away, and those who care about that period are commemorating the wars with renewed vigour. There are cemeteries honouring fallen Indian soldiers in France and Germany.

Come November, many in Britain wear a red poppy on their jackets, remembering those who died in Flanders. Rupert Brooke’s poem, The Soldier, romanticizes the sacrifice:

If I should die, think only this of me;

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.

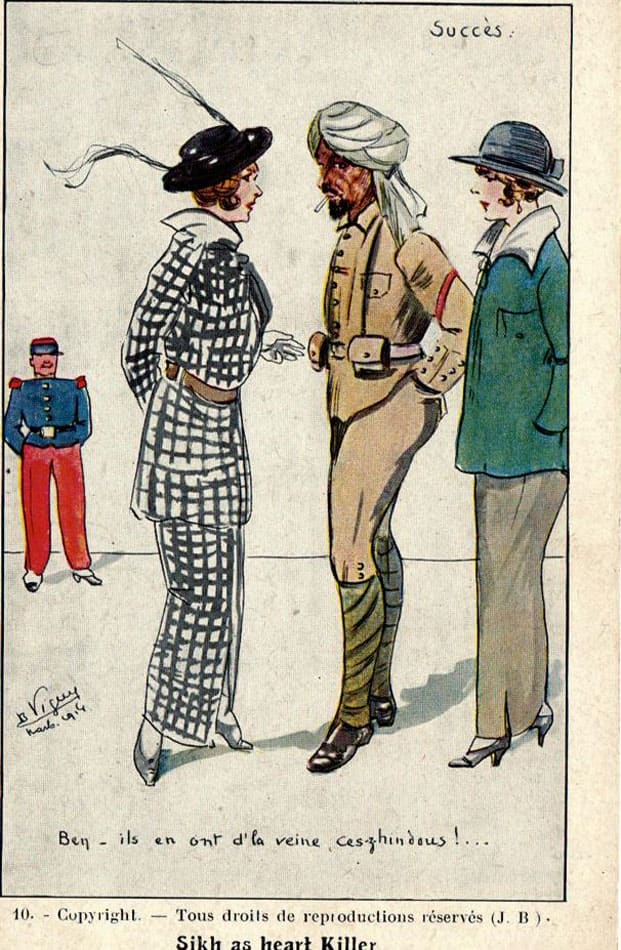

Three recent works of non-fiction and one novel, coincidentally all written by women, remind the nostalgists that those corners were not only forever England; those fields were often smeared with the blood of Pathans, Sikhs, Rajputs, and men from Garhwal and Nepal. To be sure, English villages had their own sons to mourn—foreign men who died were not forgotten, but they weren’t as easy to remember either.

If British amnesia is bad, Indian amnesia has been worse. Indian school textbooks do relate the bare outline of the world wars, but they rarely provide material that can allow students to analyse the unusual phenomenon of people signing up to fight in battles for entities of which they weren’t citizens and where they had no rights. Amitav Ghosh has written several novels which have explored the notion of loyalty—most tellingly in The Glass Palace (2000) and, more recently, in the Ibis trilogy—Sea Of Poppies (2008), River Of Smoke (2011), and Flood Of Fire (2015). He told me: “The British amnesia is far outweighed by the Indian amnesia. I think it is India that still has to come to terms with this history."

The reasons are complex. First is the question of loyalty—whose cause are the soldiers fighting for? But equally important is the question of motivation—did the men enlist because fighting for the empire was the only secure job (with pension or compensation) during the colonial time, when punitive taxes impoverished farmers, the mills of Manchester destroyed India’s cottage industry, and other factories were only allowed if they didn’t compete with British industry?

Another complicating factor is the narrative of the Indian National Army (INA)—were they renegades or patriots? Ghosh examined the INA in great detail in The Glass Palace—where tens of thousands of enlisted Indian soldiers of the British army decided to join the INA that the Japanese assembled from the surrendered troops in Singapore, and which Mohan Singh in 1942, and Subhas Chandra Bose later in 1943, commanded, hoping to invade India from the east—its march being stopped on the Indo-Burmese border in 1945.

Shrabani Basu’s For King And Another Country: Indian Soldiers On The Western Front 1914-18 meticulously recreates the personal histories of Indians who fought in World War I. She says in an email interview: “Growing up in India I was never aware that there were men in turbans fighting in the same trenches as the Tommies (as the British soldiers were known). They were illiterate peasants and did not leave behind journals and poetry like the great British war poets (such as Brooke, John McCrae, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen) did. But hidden in the archives one can find their voice, their letters and their poetry."

Historical works are often written from the perspective of the great man or woman who shapes the course of an age; more interesting accounts are those that look at the mountain peak from beneath, and Basu provides a masterly account of the war from the perspective of the foot soldiers. By retelling their stories, she re-establishes a link that had been getting frayed since independence. “The British no longer felt obliged (after independence) to remember the Indians who had fought on their side. The Indians had their own heroes to celebrate, those who had fought and died in the freedom struggle. So the soldiers fell between the two: forgotten both by their colonial masters and by their own countrymen. Their story simply faded away," she says.

Yasmin Khan’s India At War: The Subcontinent And The Second World War does the same with World War II. Not only does she bring to life the peasants who fought in the Middle East and Africa, she also casts light on the underbelly of the army—the people who kept the military machine moving—“the washermen, tailors, and boot-makers who maintained, repaired and replaced uniforms, the barbers and cooks who looked after the needs of the men, the nursing orderlies and sweepers who mopped up the camp and latrines." Many were too young to fight. In the earlier war, some boys went to knead the dough, some were syces or grooms, says Basu, who made extensive use of the letters written by soldiers from the front.

In 2014, Vedica Kant published If I Die Here Who Will Remember Me? India And The First World War, and she also built her narrative from soldiers’ letters. Ghosh points out that men from Bihar and Awadh fought for the Rajput, Sikh, Mughal, Maratha and Tamil kingdoms. Historian Dirk Kolff has argued that whoever controlled the military labour market of Bihar-Awadh essentially controlled northern India. The army was the biggest employer, and Ghosh says it became “the principal mechanism for social mobility". Many families became part of the Indian middle class because of a link with the army. You didn’t have to be a soldier, Ghosh told me: “If you ask around you will see that the families of many of your friends entered the middle class because some ancestor of theirs was a military dubash, accountant, payroll inspector, munshi or something like that. The British Raj was fundamentally a military state, there were very few options."

Besides, a military job was prestigious, and loyalty to the community, the paltan, occasionally the commanding officer, became a matter of deep faith. There was an overwhelming sense of duty and loyalty to the pledge. Basu read many letters by soldiers which mention the fact that they had eaten “the salt of the Sarkar and they must repay their debt". There were also letters warning other family members not to enlist, and a few in which it was clear that the soldiers knew they would never meet their loved ones again.

The job paid well—at ₹ 11 a month early in the 20th century, a uniform, and three meals a day, it offered a good living for peasants from a hardscrabble background. If the soldiers won gallantry awards, they got more money or land. Other rewards were emotional—one Gurkha boy, Basu says, lost his leg and an arm in a shell attack. The queen spotted him at Brighton hospital and gave him a rose.

The war was also dispiriting. Basu recalls letters she read in which the soldiers missed home and longed to go back. “They cannot fathom the war which was being fought by white people against white people. They had never seen people blown to pieces by artillery shelling. The incessant rain and cold made them depressed," she says.

It was indeed an alien war in an alien land. Kant believes part of the reason India hasn’t come to terms with its own role and contribution in the wars is because “the nature of colonial rule is still painted in very stark terms and without too much nuance". Britain, she thinks, is more aware of the colonial contribution to both wars largely because the British army was heavily drawn from specific communities. “And these communities, such as the Punjabis, are heavily represented in the South Asian community in the UK. The wars, therefore, become a moment of joint history for the diaspora communities’ own family histories and the broader history of their adopted country."

But an inclusive history remains elusive. Basu writes of Sukha, a Dalit cleaner who dies in a hospital in England. Both Hindus and Muslims refuse to perform his last rites because he is an untouchable. But a local vicar says Sukha has died for England, so he will bury him. Basu told me: “Rejected by his own countrymen, he finally found his last resting place in an idyllic village in New Forest in England. The parishioners raised money for his gravestone."

Great novels emerge from such incidents, and it was a visit to the Brighton Pavilion, and the photographs there, that helped Kamila Shamsie to flesh out the character of Qayyum in her excellent novel, A God In Every Stone, also published in 2014. Being a novel, it does not have to be encumbered or circumscribed by facts, and it is able to pursue the larger truth of what conflict does to a sensitive person. Here, a wounded soldier encounters the reality of race while convalescing in Britain, and later, learns to oppose the empire without using weapons.

Shamsie was initially interested in Peshawar’s history, the story of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, and the Qissa Khawani massacre of 1930, when the British mowed down hundreds of khudai khidmatgars, as the red-shirted, non-violent followers of Ghaffar Khan were known. She thought about the backstory of her protagonist Qayyum, one of the khudai khidmatgars, and she found that his experience as a soldier had moved him to being an anti-colonial committed to non-violence. She read about World War I from David Omissi’s Indian Voices Of The Great War and Major R.S. Waters’ History Of The 5th Battalion (Pathans) 14th Punjab Regiment, Formerly 40th Pathans.

Historical accuracy is important for Shamsie. She says: “I probably come to it from a very different angle than a historian. My thinking is, if someone who knows about the history keeps stumbling on factual inaccuracies, it’ll disrupt the feeling of immersion in the text. Every time you think, ‘No, that’s not right,’ you find yourself pulled out of the story, and feeling irritated with the author. There’s also the feeling that if all the facts are there for you to discover, why wouldn’t you? To write a novel about a subject is to enter into an obsession with it. What kind of obsession isn’t interested in the details?"

Basu, Kant, Khan and Shamsie have all relied on similar raw material—histories, letters, archives, and memories—to write their books. They have made the past more tangible, recreating it brick by brick and offering a broader truth. It is naïve to assume that four million men were driven to fight in distant lands by one singular reason. These books help us understand why.

Salil Tripathi is Mint’s contributing editor. He is the author of The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War And Its Unquiet Legacy. His collection of travel essays, Detours: Songs Of The Open Road, is out next week.

Unlock a world of Benefits! From insightful newsletters to real-time stock tracking, breaking news and a personalized newsfeed – it's all here, just a click away! Login Now!