The broken Glass Palace

Abhijit Dutta travels to the Glass Palace in Mandalay and is drawn into the colonial machinations that led to its downfall

Premium

Premium

They say all the stars fell out of the sky that night. Thousands upon thousands of glimmering arcs had shot across the black-faced vastness, before falling over the edge of the horizon. It was the Andromedid meteor shower of 1885, the starry glimmer the incandescent shards of the Comet Biela piercing through the earth’s atmosphere, but anyone who looked up at the sky in Mandalay that evening knew it was an omen.

Next morning, 28 November 1885, the flotilla that had sailed from the Madras Presidency, off the coast of Coromandel, crossing the Bay of Bengal and coursing up the Irrawaddy, past unfinished fortifications and half-done stockades, reached the banks of Mandalay. It was common enough for ships to come up to Mandalay—it was the royal capital—but they did not carry cavalry troops or have machine guns mounted on them.

***

When I think of Mandalay, I think of the ransacking of its palace. It is to do with Amitav Ghosh: A scene from his novel, The Glass Palace, has remained vivid in my mind—“The chamber was very large and its walls and columns were tiled with thousands of shards of glass. Oil lamps flared in sconces, and the whole room seemed aflame, every surface shimmering with sparks of golden light. The hall was filled with a busy noise, a workmanlike hum of cutting and chopping, of breaking wood and shattering glass. Everywhere people were intently at work, men and women, armed with axes and dahs; they were hacking at gem studded Ook offering boxes; digging patterned gemstones from the marble floor; using fish-hooks to pry the ivory inlays from lacquered sadaik chests. Armed with a rock, a girl was knocking the ornamental frets out of a crocodile-shaped zither; a man was using a meat cleaver to scrape the gilt from the neck of a saung-gak harp and a woman was chiselling furiously at the ruby eyes of a bronze chinthe lion...."

And now I have wandered into this room in the clear light of day. It feels odd, stepping barefoot around this room—62ft-something between floor and ceiling, 100ft from east to west. I feel I am trespassing, even though I have paid the 10,000 kyat (around Rs530) fee for the Mandalay zone, a ticket foreigners must buy to access the main sights in Mandalay—its many pagodas and this one palace. I look about the cavernous emptiness and think I have arrived just as they have left, the looters, the vandals. The place feels hollow, like the pit of a stomach in fright, held up by these teak posts the colour of betel spit. No, that’s not right. They were teak. These are reinforced concrete, a sheath of teak hugging it. In 1989, when they were breaking down walls in Berlin, in Mandalay they were trying to put back what was destroyed in 1945. The long tail of a world war—it grows a wall here, grinds to dust a palace there.

But the palace in Mandalay had been done in long before the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service flew in with its firebombs. The palace was destroyed in November 1885, when the British put Thibaw and Supayalat, king and queen, last of a line called Konbaung, on to ox carts and dragged them through the dusty streets of the walled city and out of its west gate, the gate through which the dead were taken out, and on to the Gaw Wein jetty, where they were put on a steamer and sent to India to live out the rest of their lives on a hilltop bungalow with a view of the sea.

The British turned the palace into a fort and called it Dufferin, after the viceroy of India, who added, to his already extensive titles, “Marquess of Ava", taken from the “Court of Ava", as the royal court in Mandalay was called. Really, what did the Japanese destroy with their bombs and arson that the British hadn’t that day in November when they walked into the palace with their shoes on, and told poor Thibaw that his time was up and that he would be leaving Mandalay forever.

And why blame only the British, it was proper intrigue, involving pukka schemers and double agents, the roil of global politics—an insurrection in Zululand, the shooting in Kabul, French adventures in Indochina—and the wily machinations of global corporations.

In this room there is no trace of that history, none of the sweep and swirl that led to the fall of the last king of Burma—except for a statue of the king and his queen, seated in traditional style—folded knees, feet tucked under their haunches—on a raised platform. The room is otherwise so barren that they seem painted into a corner, cast away to a terrible isolation, exiled in the very room that was once the centre of the universe. Maybe it is only right that most tourists who come looking for the refractive splendour of the Glass Palace are underwhelmed by the sad bits of glass stuck on the wall because that name in fact has nothing to do with the decoration. They called it the Glass Palace because it was the Central Palace; the position of every other building in the palace grounds was fixed by glass-marking from this centre.

There is nothing else to see in this room and the light is too dim for good photographs. I turn around and walk out. Once outside, I put down the flip-flops I have been carrying in my hands and slip my feet in. It’s the custom in most of the places one visits in Mandalay, certainly in the pagodas, and I had simply assumed it was the case here too. I am glad, because I now see the little signboard I had missed on my way in. “No footwear allowed," it says. I take a photo of this and allow myself a chuckle.

***

They called it the “Great Shoe Question". It may be too much to say that the British empire went to war over shoes but it is certain that they were a thorn in its side. Every chronicler of the time whined about the treatment meted to them by the king of Burma, who wanted British officers to enter barefoot and shiko, sit on folded knees and touch the ground with their foreheads as greeting. It was a matter of protocol for the Burmese, and these things mean so much to kings, but to the British it was simply intransigence. “…although the Burmese Government ‘wished for peace’, it declined to settle the ‘shoe question’," wrote Colonel W.F.B. Laurie in his book Our Burmese Wars And Relations With Burma. “It does seem eminently absurd, the political officer of Her Majesty the Empress of India appearing before the Golden Foot without his shoes!"

And since king Mindon, father to Thibaw and the founder of Mandalay, could not yield to the suggestion that he dispense with a ceremony so intrinsic to his status as the “Golden Foot", and the English representative at the court couldn’t afford to reduce his own status by “squatting unshod" and “creeping barefooted", it soon came to be that there was no representative of the Indian government at Mandalay and communication between British Burma and the Court of Ava dwindled to hearsay and half-truths. The only channels by which the British kept themselves apprised of the goings-on in Mandalay were a postmaster who, for a fee, wrote them a periodical newsletter and the Italian consul, Signor Giovanni Andreino, to whom nothing that went on in Mandalay was unknown.

The annoyance over the shoe question masked a greater irritation. Ever since the British took Pegu in the unprovoked Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852-53)—and fixed a border between Burmese-ruled “Upper Burma" and British-ruled “Lower Burma" such that the richest teak forests fell to the British—it became increasingly clear that British mercantile interests were growing impatient. A commercial treaty was signed in 1862, and another in 1870, but they were not enough. “By ancient customary law, the King was the owner of all forests, oil fields and mines," and therefore Mindon was the sole exporter of timber, oil and rubies—something the English merchants begrudged greatly and described as a monopoly. What the English hated most was the licensing system Mindon had introduced when it came to trading goods outside the country.

Then, as now, the prize was China, and Burma happened to be the back door and a hindrance. As early as 1867, the secretary of state in London was writing to the governor general in India that it was of primary importance to ensure no other European power could insert itself between British Burma and China. Archibald R. Colquhoun, a self-styled China expert whom the Royal Geographical Society had awarded a gold medal “for his journey from Canton to Irrawadi" and who was the author of books such as China In Transformation, wrote a new best-seller in 1885 and called it Burma And The Burmans, Or, The Best Unopened Market In The World. “The opening of this market," he wrote, “would be a bright prospect for our merchants in British Burma, and for the manufacturer at home; and an immense field for the British capital would be thrown open. Trade routes already exist..." Colonel Laurie argued similarly: “If we do not, for the sake of peace in Eastern Asia, so effectually settle Upper Burma, before very long, Russians, and even Germans (on account of China) will probably be ‘doing business’ at the capital of the Golden Foot. There is a great game of chess being played all over the world; and Britannia must not allow herself to be checkmated."

London was reluctant, its plate was already full. There was trouble in Afghanistan—the Great Game was in motion and the threat of a Russian coup de main was never far from the British mind; an uprising in Kabul had led to the slaughter of the British representative; and the governor of Herat had revolted and laid siege to Kandahar. In South Africa, the fight with the Zulu was not progressing smoothly; the rag-tag tribal militia had put up stiff resistance. And although Colquhoun assessed that “the military power of Burma is at best but a very badly managed piece of humbug, deceiving no one", for the viceroy in India, a war with Burma would be “a last resource".

***

In my hotel—which sits just across the palace walls off 26th Street—the breakfast tables are full of French tourists. In recent times, the numbers of Chinese and American tourists have begun to crowd the top of tourist arrival charts but the French still make up the biggest group from Western Europe visiting “Birmanie". It’s an old connection. Burma was never a French colony like Vietnam, but the French presence has always loomed large.

In the last decade of Mindon’s rule, a Burmese embassy had made its way to England, in the hope that a treaty may be negotiated with the queen herself, confirming the status of the Court of Ava as a sovereign kingdom rather than an annexe of British India. It was a grand itinerary, their diary full of merry balls and races and cricket matches and sightseeing (Madame Tussauds, of course, and the British Museum; also prisons, asylums and hospitals). They visited the industrial towns of Birmingham and Manchester; they were hosted generously in Dublin and in Glasgow. Herbert White, a British civil servant, found it all too much. “To us who realize the insignificance of the King of Burma as a potentate, these proceedings savour of the ridiculous," he wrote in his memoirs.

That view would certainly explain why, despite all the gaiety and the glitter of their reception, a year passed and only one audience had been granted with Her Majesty, with no talk of a treaty. Even the lone meeting proved counter to the purpose: The Burmese delegation had been presented to the queen not by the foreign secretary, as would be appropriate for an embassy of a sovereign kingdom, but by the secretary of state for India. Mindon, impatient now, ordered the delegation to Paris. By Christmas, the Burmese embassy had been to see the French president in Versailles and signed a treaty. It wasn’t terribly significant in terms of its provisions—it was a mere commercial treaty, not a treaty of alliance—but it was still a signal to England: We have other friends.

British wariness of French designs on Burma went back a long way. Their naval rivalry in the Indian Ocean had been the thread that tied the three Carnatic Wars together, their armies fighting off the Coromandel Coast while the respective East India Companies tore at the trading posts of Madras, Pondicherry and Cuddalore. “Did the French have expansive ambitions in the Bay of Bengal?" was a question that kept the British up at night.

In 1872, when the Burmese embassy first visited Europe, the French were still recouping from a nasty defeat Prussia had handed them in a war just a couple of years ago. They had neither the appetite nor the interest to rankle London—there was bigger fish to fry with them over the French settlements in India. Burma, they hemmed and hawed to the British ambassador in Paris, was of interest only because it was close to Cochinchina (Saigon), a French colony. Despite some controversy about the question of supplying French arms to Mandalay, the treaty of friendship and commerce was duly signed and a French embassy proceeded from Marseille for Mandalay, to have it ratified at Mindon’s court. It was not to be. Despite the endless fawning and ceremony at Mandalay, the treaty remained unratified. It is likely that Mindon got cold feet. To the British resident at Mandalay, the king said, “I have not ratified the French Convention. The French will give me cannon, arms, etc., but I would prefer to get it from you."

While the discussions were on, the French continued to be treated with much pomp. This long stay made the Italians jealous, not least the consul Andreino. Andreino wasn’t yet the lynchpin of an international spy ring that he would be in a few years, but he was still a schemer. He whispered into British ears that the French were about to win major concessions from Mindon—ruby mines and prize timber in return for arms and ammunition—and the rumours carried.

***

Andreino was a mysterious man. A village blacksmith from Naples, he had arrived in Burma soon after a treaty signed by Mindon in 1871 with the Italians. Andreino had family in Burma; his brother was a Catholic bishop in Mandalay. He became, in the first instance, the Italian consul at the Court of Ava but the full extent of his influence seemed unknowable. Besides the British, who counted on Andreino for palace intelligence, and the French, who also trusted him, he was a paid lobbyist for the biggest business houses of the time—the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation, the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company and Finlay Fleming, and to them lay his greatest loyalty.

The attempt by Kinwun Mingyi—the senior minister who had led the Burmese mission to Europe—to establish a commercial treaty between the French and the Court of Ava in 1872, and then again in 1874, had failed but—contrary to the assessment of the British ambassador in Paris—was not “without a hope of resurrection". Mindon died in 1878 and his son Thibaw, still in his 20s, came to sit on the Lion Throne. It had cost some 70-odd relatives their lives—they were clobbered to death, wrapped in blankets so as not to spill royal blood—and it caused an uproar in Rangoon and London. In fairness, murdering your kith and kin for succession wasn’t something Thibaw had invented; the English displeasure, given their own past, seemed a bit out of proportion and an idea very much in the mould of Oriental Despotism.

Truth was there was more at stake and it was commercial in nature. British merchants simply didn’t like the new king and it helped to talk of him as a tyrant and a drunk unfit to rule. The administration was corrupt, they cried. Business was being hampered, they cried. He can’t keep law and order, they cried. A new treaty of commerce was negotiated in Simla in 1882 but agreement couldn’t be reached about who the treaty was with—Her Majesty’s government in London, as the Burmese desperately wanted, or merely the Indian government in Calcutta. Thibaw even went as far as to offer that the British representative in Mandalay would be received complete with shoes and sword. This was still not acceptable and slowly but surely the negotiations crumbled. Frustrated with the British refusal to accord Ava sovereign status, Thibaw did what his father had done. He sent an embassy to France, and as a first step ratified the agreement that Mindon had not.

When the first French consul, Frederic Haas, arrived in Mandalay, in June 1885, rumours reached their apogee. The treaty had secret clauses, it was whispered. Major concessions were being made to the French—railway lines, a bank, the royal ruby mines—in return for arms. Britain was being cut out; the French were moving in. There was no real proof of any such thing but mysteriously, papers were obtained—some say forged—by Andreino that suggested it was all possible.

In this vexed atmosphere of suspicion and intrigue arose a practical matter: The Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation was fined a sum of Rs23 lakh. The court of Ava alleged that the corporation had evaded tax and duties on some 56,000 logs that it had sent downriver to its sawmills from the forests of Ningyan. If the corporation didn’t pay up, Mandalay would cancel its licence to log. The corporation alleged that the feckless king had run out of money and had tapped them for a loan, which had been denied; this was revenge.

Andreino, who had the Corporation’s interest very much at heart, being its lobbyist, knew that the only way to get the Indian government to move against Thibaw was the spectre of a French threat. To the talk about ruby mines and banks and railways, he added timber. Monsieur Haas had reassured Thibaw, Andreino told Rangoon, who told Calcutta, who told London, that should it be required, French firms could step in to work the teak forests. It was an incendiary mix and moved Whitehall, finally, to action.

In the end, it all happened too quickly. The British despatched an ultimatum on 22 October, essentially demanding that the king place Burma as a feudatory of British India, receive a special envoy at the court—with his shoes on!—to settle the matter of the British Burmah Trading Corporation; and place no restriction on British trade with China through Upper Burma. A written acceptance was to be received by 10 November or else. The steamer carrying the ultimatum reached Mandalay on 30 October. On the 31st, Kinwun Mingyi presented it in the assembly. Thibaw was in shock and his ministers in different minds. Some ministers, like the Taingda Mingyi, advised him to reject it and declare war. The Kinwun Mingyi, wisened by his travels to Britain’s military superiority, counselled acceptance. It was a deadlock. Thibaw, it seemed, was inclined to follow the Kinwun’s advice. He remembered the prophesy the royal astrologers had made years ago—he would be the last king of Burma, they had said. Then his queen, Supayalat, pregnant with child, spoke.

The Kinwun Mingyi was not a man, she roared. He was “an old woman, an old, old, old woman". Then she asked the maids to bring the minister a woman’s skirt and a fan; “the Kinwun Mingyi shall go live amongst the women". It seemed impossible to argue reason in the face of Supayalat’s feral call for war and, ultimately, she prevailed. He rejected the ultimatum. The answer was received in Rangoon on 9 November, two days after Thibaw had issued a royal proclamation in Mandalay; there might be war, he told his subjects, and they should keep calm. He would defeat the English and seize their country.

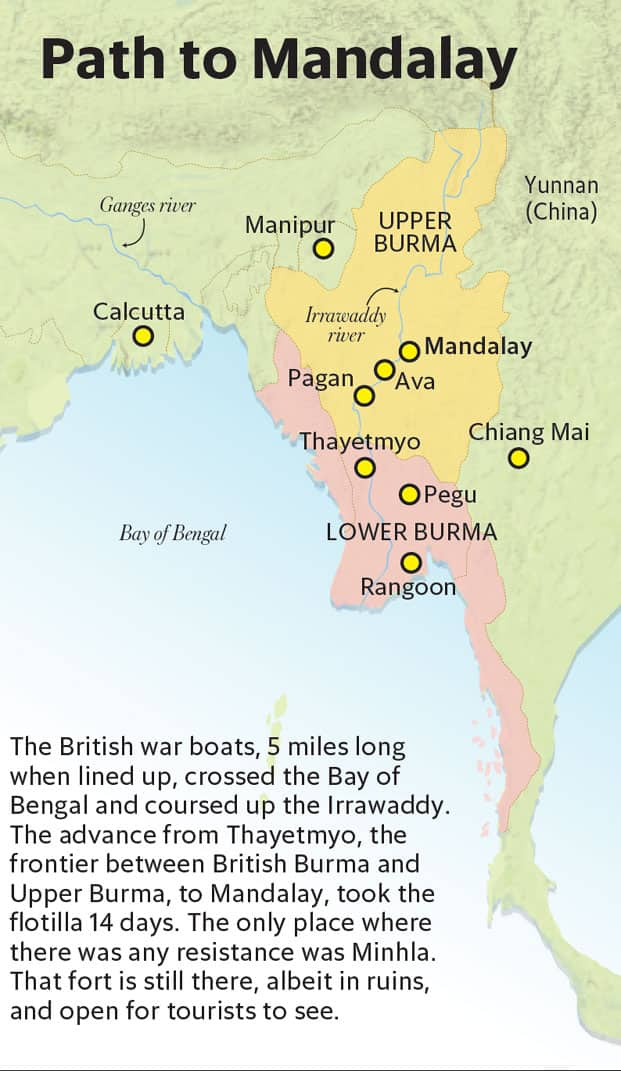

Steamers, provided for the purpose by the privately-owned Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, which would be among the biggest beneficiaries of increased upriver movement of goods to China, had been turned into war boats. Mounted with machine guns and carrying troops (most of them Indian natives of the Madras Cavalry), they had already reached Thayetmyo, some 400 miles from Mandalay, and stood waiting, like a plague of locusts. They crossed into Upper Burma on 14 November, commanded by Major General Prendergast, and travelled towards Mandalay. The town of Minhla was breached and its Italian-built fort occupied on the 17th, the ancient town of Pagan, the first capital of Burma, taken on the 23rd, and by 25th the flotilla had crossed Myingyan. As Colquhoun had predicted, no “drastic measures" were required—except for Minhla, where there was some brisk fighting, the progress was unhindered and resistance scarce. From complete denial of what was in progress, Thibaw and Supayalat now grew fearful of what seemed inevitable. Even before the British reached Ava, the Kinwun Mingyi was despatched to negotiate a dignified but unconditional surrender. Ava and Sagaing were then given up without demur on the 26th and 27th, and the ships travelled all night under a sky lit with meteoroids hurtling through the atmosphere. On the morning of the 28th, General Prendergast occupied Mandalay. Colonel Sladen, the chief civil and political officer of the Burma Commission, entered the palace to tell Thibaw, sitting nervously on the Lion Throne one last time, that it was all over.

That night, as his palace was being looted, he slept in the Summer Pavilion out at the back, surrounded by British guards. The next day he climbed on to an ox cart and left the palace in Mandalay, drawing the curtain on the third Burmese empire, which at its height had ruled all the lands from Manipur to Chiang Mai.

***

The Mandalay Palace is now more cantonment than royal city. Taking a leaf out of the book of the British, who had turned the complex into Fort Dufferin soon after the invasion, and the Japanese, who turned it into a garrison during their occupation, the Myanmar armed forces—the Tatmadaw—have turned the palace grounds into residential quarters for themselves and their families. Gates on three sides have restricted entry—only the Tatmadaw and its families may enter; all others may enter through the East Gate.

I cycled about the compound, ignoring signs that advised me to keep off and stick to the palace complex. It wasn’t rewarding. The whole place seemed no more than a sleepy village, the occasional hunting-green jeep or truck the only hint of army presence. Untidy shrubs crowded the grounds, trees stood tall. A mother suckled her baby in the shade. A dog licked its wound. A solitary cast-iron cannon stood surrounded by untrimmed bush and beautiful designs. A rabble of yellow butterflies faded into the white afternoon sun.

None of it—the columns, the throne, the rooms and halls (and there are so many)—is original. The Japanese bombing, and then arson, in World War II took care of that. Of the nine thrones that Mindon had had built for his new capital in 1858, only one survived the war; it is now kept at Yangon, at the National Museum. Mandalay itself is now simply the second largest city of Myanmar, no more. The pretender to the tradition of royal capital lies south of it, Nay Pyi Taw, about which much remains to be written, and its predecessor, Yangon—or Rangoon or Dagon, depending upon how far back you want to reach—still remains the first city of Burma.

Reconstruction work on the palace was begun by the military government in 1989—soon after the famous uprising of 1988 (what does that say?)—and over 400 wood carvers and 320 unskilled labourers worked 10- to 14-hour days to recreate over a hundred buildings that comprised the original complex. It was a massive undertaking, a delicate balance of new and old.

I knew walking up the flight of stairs that leads from the front gate to the Great Audience Hall that the floorboards were still teak, although their width of 4 inches is a third of what it was in Mindon’s time. Still, courtesies were maintained—all the teak used was seasoned for a year, as it should be, and its bark removed, before being cut. I relished its polish beneath my feet—yes, bare feet. In the room behind the audience hall, I brushed away a layer of dust on the red tile floors with my hands, and the colour deepened. They were recreated by mixing ferrous oxide with cement, and applied to the poured cement floors while they were still wet. In some inner surfaces, the gilt coating is plastic gold from Japan.

It is easy to cry over the use of charmless modern materials but, as Elizabeth Moore points out in her interim report on the construction, this is in fact a “philosophy in keeping with centuries of cyclic restorations". The kings of Burma have a long tradition of moving their capitals and these moves were quite literal. When the royal capital was being settled in Amarapura, in the 18th century, the buildings erected used many of the teak structures from the buildings in Ava, a capital that was older still; when the kingdom was moved back to Ava—and again when it was finally reassembled in Amarapura—many of the structures used were already extant. Mindon’s Mandalay, constructed in 1857, used teak parts that had been a part of the palace buildings for at least half a millennia. However, it also added embellishments and new paint and gilding. “…from its inception, Mandalay Palace has combined recycled structures with new parts," wrote Moore. The modern modifications are practical improvements and part of a long history of continuous renovation and restoration. Besides, it is better for fragile hardwood forests, suffering from the deforestation caused by relentless logging and timber smuggling.

I wandered about the precincts camera in hand, trying not to photobomb any selfies. I was surprised by how many locals had come to see the palace, their numbers greater than foreign tourists. I wonder what they make of it—this attempt at holding together the remains of a kingdom—even as their country makes its way through the complexities of today’s more urgent reconstruction. Aung San Suu Kyi’s recent “embassy" to Washington, DC, was certainly more fruitful than the Kinwun Mingyi’s to England in 1872.

Earlier in the week, I had done what most tourists who arrive in Mandalay do—take the full day “Ancient Capitals Day Tour". In less than 8 hours, you can skip across 700 years—first stop at Ava, then Sagaing, both 14th century royal capitals; then lunch at a traditional Burmese eating joint in Mandalay; enjoy the journey across the Irrawaddy to Mingun, not a royal capital but home to many large things built by fanciful kings—a 90-tonne bell among them, second only to the one in St Petersburg; and then, for a view of the sunset, to the photogenic U Bein Bridge in Amarapura, a two-time royal capital.

In each of these places, I tried hard to see past glory. The guides tell you the story, plaques with gilt lettering back up their claims. Yet before my eyes are simple-looking villages, muddy tracks wet with rain, broken bits of brick, weeds, moss, cobwebs, dust. The teak has lasted—a monastery in Ava that is more beautiful than the thousand golden pagodas I have seen in Burma—but little else.

Leaning over an old teak post on the U Bein Bridge, watching the sunset darken to an indigo evening in which everything becomes shadow, I think of my travels through the country. These days Myanmar itself feels like a restoration project. Its airports, once the busiest in the region, are once again stirring with a great hum—the new terminal at the Yangon international airport has the same soft hush and quiet gleam of Singapore’s Changi Airport (not a coincidence—the Changi Group won that contract); plans for roads and bridges and peace conferences are being built to once again “unify" the country, to pull it into a tight weave, sharpen the outer borders but soften the ones inside; the new-ish capital, Nay Pyi Taw, that invokes the history of the capitals that came before—Aniruddha’s Pagan, Bodawpaya’s Amarapura, Bayinnaung’s Ava, Mindon’s Mandalay. There is of course a difference between restoration and replication—the Uppatasanti Pagoda in Nay Pyi Taw copied, poorly, from the Shwedagon Pagoda is an example—and it will take curious visitors from the future to look around the capitals that this century will leave behind, and wonder how many layers of truth and legend and history and memory lie beneath the stucco on the walls.

*****

In other rooms, other wonders

The Mandalay Palace is in fact a palace-city, girded by a square perimeter of red walls around 3km on each side, with a moat. At the time it was built, the whole city of Mandalay lived within these walls, about 120,000 people, in bamboo huts—many of them ‘kala’, those who had come from across the sea, like Indians.

The palace complex itself was a much smaller area, although it had over 100 buildings, the grandest of which was the Great Audience Hall, made wholly of ‘yamanay’, a rare type of light wood. Here stood the Lion Throne, one of nine, but the most prestigious. To reflect its status as the royal seat, the Hall had a seven-tiered roof, ‘pya-that’, soaring over it. As you walk about the complex, it is the ‘pya-that’ of the Great Audience Hall that orients you. It is where visitors were received, including the consuls of the various diplomatic corps, the equivalent of the ‘durbar’. Depending upon the relations with the British at any time, the polished teak floor would either be heavily carpeted or left bare, with nails sticking out.

Nearby is the Hall of Victory, where sat the Goose Throne, and where matters of grave threat to the kingdom were discussed. No doubt, Thibaw would have huddled here with the Kinwun Mingyi and the Taingda Mingyi in the days leading to the war. A smaller Promenade Hall, open to the breeze, is provided for the king to stroll about, and was well staffed with retainers whose job was to present betel nut and water whenever he wanted it. The Baungdaw Saung, with its three-tiered ‘pya-that’, was where the royal ornaments, gems and jewels were kept; looters that night would have found the richest haul here.

*****

Unlocking the Burma box

Selected bibliography on the British invasion of Burma, Anglo-Burmese relations, and the history of Mandalay

■Thant Myint-U, River Of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History Of Burma

■ Htin Aung, The Stricken Peacock—Anglo-Burmese Relations, 1752-1948

■ Elizabeth Moore, The Reconstruction Of Mandalay Palace: An Interim Report On Aspects Of Design

■Herbert Thirkell White, A Civil Servant In Burma

■ Shway Yoe, The Burman—His Life And Notions

■ Archibald R. Colquhoun, Burma And The Burmans, Or, The Best Unopened Market In The World

■ Htin Aung, Kinwun Mingyi’s Mission To The Court Of Versailles, 1874

■ Colonel W.F.B. Laurie, Our Burmese Wars And Relations With Burma

■ Nicholas Tarling, Imperialism In Southeast Asia—A Fleeting Passing Phase

■ A.C. Pointon, The Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation Limited, 1863-1963

■ J.H. Titcomb, Personal Recollections Of British Burma And Its Church Mission Work In 1878-79

Unlock a world of Benefits! From insightful newsletters to real-time stock tracking, breaking news and a personalized newsfeed – it's all here, just a click away! Login Now!