Jazz on Churchgate Street

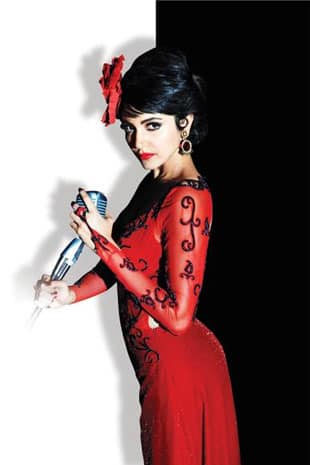

Bow ties, Lobster Thermidor, tipple in a teacup and Chris Perrythe look of Anurag Kashyap's forthcoming film reminds us of Bombay's gilded age

Premium

Premium

In the late 1950s, probably 1958, a new restaurant opened in the Kala Ghoda area in Bombay. Built over two levels, La Bella, as it was called, was set up to compete with the fancy joints of Churchgate Street (now Veer Nariman Road)—The Ambassador hotel, Gaylord and Volga—and round the corner from them, The Ritz hotel and Astoria Hotel. These were the regular watering holes for the city’s elite. Each of these restaurants boasted of a top band, a popular singer and a cabaret dancer—La Bella’s owners decided they would go one up and import not just the entertainers but also the chef, who came from Germany.

I grew up hearing stories of La Bella from my father, who was the manager there. He had arrived in Bombay from Karachi via Delhi and got a job, first in Astoria and then La Bella. He spoke of the glamour-filled nights, of the Ceylonese cabaret dancer, the British sextet (the Margaret Mason band) and the elite—industrialists, socialites, film stars like Raj Kapoor and Dilip Kumar— who thronged the place every night. Old photos show him and the guests in the fashionable attire of the time—sharp suits, bow ties, slicked-back hair. In the fancier restaurants, black tie was the norm. The ladies wore mostly saris but also gowns, and, if very daring, trousers—smoking by women was not unheard of. It is easy to imagine the tinkling of the piano, the roar of the trumpet and the dulcet tones of the crooner in the background.

It is this glittering universe that Anurag Kashyap has tried to replicate in his film Bombay Velvet, which is releasing in theatres on 15 May. It is apparently set in the Bombay of the 1950s-1960s—the official trailer gives us glimpses of the gowned singer, the six-piece band, patrons dressed to the nines. Kashyap reimagines a Bombay of trams, streamlined Cadillacs and sinister, Fedora-wearing men, scowling at everything through the haze of blue cigarette smoke as they search for a photo negative—clearly, he has noir on his mind.

Bombay of the 1950s and 1960s is a time well-remembered by many who insist it was the Golden Era of the city’s history: when the city was carefree, leisurely, clean, and most of all, liberal.

In Bombay, Churchgate Street was at the epicentre of the entertainment quarter that extended down to Flora Fountain and then beyond to Kala Ghoda. The names of the restaurants told their own story; apart from the ones already mentioned, there was also Napoli, Bistro, Gourdon, Bombelli’s and Venice in Astoria Hotel, all redolent of an easy, cosmopolitan sophistication. Bombay thought of itself as just another link in the chain that extended from New York to London to Paris to Beirut and Cairo, and then to Hong Kong.

Further south from Churchgate, near the Gateway of India, stood the magnificent Taj Mahal Hotel, where a series of well-known jazz musicians played. Close by were The Mandarin and Alibaba, famed for their cabaret acts, which usually involved an exotic dancer in ostrich feathers or sequins and often ended with her stripping down to as much as the law allowed. Blue Nile at New Marine Lines boasted of the charms of Tamiko the Tomato, said to be of Japanese origin. Nataraj Hotel (now the InterContinental on Marine Drive) had the cabaret dancer Corrina as the main attraction.

Some of these establishments were run by expatriates. The Ambassador hotel, for instance, was presided over by Greek restaurateur Jack Voyantzis, a giant of a man known for his penchant for cigars and the ladies. Bombelli’s was presided over by the Swiss Freddie, and Gourdon’s was founded by the European Emile Gourdon. The “look" of many of these restaurants—chintzy sofas, velvet curtains, liveried waiters—lasted well into the 1970s, even after the Jazz Age had long ended.

Many of these restaurants were home to the well-known bands of the time. Names of artistes like Ken Cummine, Dorothy, Dinshaw Balsara, Chic Chocolate, Tony Pinto, Johnny Baptista and the flamboyant Chris Perry are familiar to Bombay’s old-timers. They played mostly jazz standards and the popular love songs of the time—Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra and occasionally, one of their own compositions. Hindi music was verboten.

The menu offered both Indian and “Continental" cuisine. Most of those dishes have vanished for the most part from the culinary landscape of Indian cities—Steak Diane, Chicken a la Kiev, Lobster Thermidor, Prawn Cocktails, Minestrone Soup, and that staple that was the first introduction of many Indians to foreign food, Russian Salad.

The one thing missing from this la dolce vita (the sweet life) was booze. Bombay was in the throes of complete prohibition. When the puritanical Morarji Desai took over as chief minister of Bombay state in 1952, the Bombay Prohibition Act, 1949, was imposed with even greater fervour. Liquor was available only if one had a permit, which could be obtained, with difficulty, for medical reasons. Not surprisingly, the number of unwell people in Bombay who just had to have a drink kept growing constantly. The others could either go to any of the innumerable “Aunty’s joints" in the seedier parts of town, where they would be served moonshine and boiled chickpeas and boiled eggs. The well-connected had their own bootleggers, who promised to get the best foreign whiskies though there was never any guarantee it would be genuine. Some accounts speak of restaurants serving alcohol in teacups, all the better to enjoy the cabarets.

This club scene often echoed in the noirish Hindi crime films of the time, films by directors such as Guru Dutt, Raj Khosla, Vijay Anand, Shakti Samanta and Nisar Ahmad Ansari. Movies like Baazi, C.I.D., Kala Bazar, Howrah Bridge, Black Cat and many more, were inspired by Hollywood crime films but were strongly rooted in the Indian idiom. No director would risk making a film without songs, a comedy track and emotional drama of the kind Indian audiences expected. Yet, though these were Hindi films, the influence of a Western sensibility was plainly visible and came through most starkly in the club scenes.

The nightclub in these films was usually a den of criminals, the nefarious front behind which the shadowy boss operated. The boss’ moll—Julie, Lily, Maria, Sophia—was the lead dancer, backed by a chorus line, which was composed mainly of Anglo-Indians, who almost totally monopolized the Western dance segment. It was here that the hero came to look for whatever he was looking for—the smuggled goods, the stolen statue, the murder accused. The club dance provided the director an element of exotica, providing the front-bencher a peek into the lives of the metropolitan rich and, by implication, of decadence.

Going by what has appeared in the public domain so far, Bombay Velvet (whose lead singer is called Rosie) draws on all those elements—the real and the fictional, even if it is a much modernized and shinier version. The outfits and sets are designed to perfection and the film-makers have even used a song from the Dev Anand-starrer C.I.D.—Jaata Kahan Hai Deewane by Geeta Dutt—remixing it to appeal to a younger demographic, though it is debatable if the new version improves upon the original (ironically, the song was not used in the 1956 film). Looking for verisimilitude will be pointless—there were no professional street fighters or Tommy Guns in the 1960s or at any time. Also, by the mid-1960s, the clubs of Bombay were undergoing a shift—pop bands, inspired by The Beatles and other more youthful groups, were slowly taking over; soon they would come to dominate. But this is Kashyap’s imagined version, not lived history or a truthful retelling.

Will today’s audiences, far removed from the real 1950s and 1960s, take to it?

Sidharth Bhatia is a journalist and author and is currently writing a book on Bombay noir crime films.

Also read Ten great jazz-related moments in cinema

Unlock a world of Benefits! From insightful newsletters to real-time stock tracking, breaking news and a personalized newsfeed – it's all here, just a click away! Login Now!