Connemara: An Irish Taj Mahal

Kylemore Castle, once home to an epic love story, and the place where two Indian princesses studied, is now cared for by nuns

Premium

Premium

Miles and miles of hillsides dotted with black-faced Connemara sheep pass by as the tour guide drones on in his incomprehensible Irish accent. Suddenly, his practised routine is replaced by an excited, “Here it is, look to your left." All heads turn, and there is a collective gasp. We have caught our first glimpse of Kylemore Castle, a medieval-looking stone structure.

The bus pulls over, and we all step out. There is a nip in the air, and I pull my jacket closer, rushing past the Pollacappul lake shimmering with the reflection of the castle and the gigantic, rugged mountains that gird it.

This 70-room castle, with a neo-Gothic cathedral—the Kylemore Abbey—and acres of landscaped garden, was built as a paean to love by a Manchester surgeon for his wife. A Taj Mahal of Ireland, so to speak, created during the wife’s lifetime.

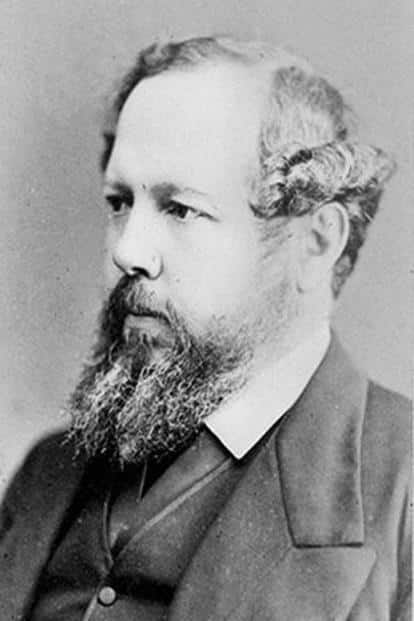

In the late 1840s, Mitchell Henry, son of a wealthy textile businessman, visited Connemara in western Ireland with his bride, Margaret Vaughan, on their honeymoon. Margaret fell in love with the place and dreamt of raising a family there. In 1862, after his father died, Henry bought 15,000 acres of land in Connemara with his inheritance and built the Kylemore castle as a gift for Margaret.

Like the Taj Mahal, Kylemore cost a fortune, but unlike it, it didn’t end with the local workers losing their hands. In fact, it came as a blessing. Connemara was then recovering from the dreadful Irish famine. A third of its population had died of starvation; the survivors were struggling to eke out a living. With its vast bog lands, however, Connemara was unsuitable for farming. Hundreds of survivors of the famine, then, found well-paid employment as construction workers for the monumental creation of the castle.

Henry’s extravagance wasn’t limited to himself; he spent generously on the town. He built a post and telegraph office near the castle, erected a village pump and set up a school for the children of his tenants.

With his innovative and industrious ways, Henry turned the bog wasteland into fertile ground. Fruits, vegetables, dairy, meat and bread of the finest quality were produced on the estate. Family, friends and dignitaries from England were invited to stay at Kylemore and enjoy the comforts of the estate.

But the good times didn’t last long. In 1874, Margaret, 45, died of dysentery while on a family holiday in Egypt. Heartbroken, Henry brought her body back to Kylemore and laid it to rest there. In her memory, he built a neo-Gothic church next to the castle.

It’s a short walk from the castle. On my way there, I am accosted by the chirping and song of birds. The tree–lined path continues around a bend, dense foliage sheathing the view beyond. It leads to a nature trail that I want to explore. The 2 hours allotted to this vast estate suddenly seem too little, and I remember the tour guide’s words, “Use the time wisely." I decide to heed his advice and enter the church.

The pews are packed with people listening to a student choir visiting from the US’ North Carolina State University. There is a reticent dignity about the place. But for the singing, it is serenely quiet.

A slender statue of Christ on the front glass window is so perfectly aligned with the frame that one can easily miss it. Sandstone arches on the sides and ceiling of the church are carved intricately with flowers, birds and smiling angels—feminine features added as a tribute to Margaret.

As the story goes, Henry’s philanthropic nature eventually led to his downfall. He lost most of his fortune, and, by the early 1900s, Kylemore estate was heavily mortgaged. The castle and the estate were put up for auction. Henry went back to England, leading a modest lifestyle there until his death in 1910. His ashes were buried in Kylemore.

Margaret and Mitchell’s deaths brought to an end a glorious chapter in Kylemore’s history. The estate was to change hands many times thereafter. It was as if the castle was trying to find an owner as deserving as the Henrys.

The new owners of the estate, the duke and duchess of Manchester, friends of the Henrys, were already in massive debt. The purchase of the Kylemore estate in an auction, and its upkeep, was financed by the duchess’ father, a wealthy American baron. After his death in 1914, Kylemore was sold to a banker from London who rarely visited the place and left the vast estate in the hands of a caretaker.

In 1920, Kylemore found itself a new owner again. This time, it was the nuns whose Benedictine Abbey in Ypres, Belgium, had been destroyed during World War I. The nuns bought the estate and set about restoring the place to its former glory.

They turned the castle into an international boarding school for young women, using the main bedrooms as classrooms and dormitories. They taught the girls subjects ranging from history, mathematics and languages to Christian doctrine. As the school gained in reputation, it attracted young women from close and distant lands, even as far as India.

The inner hall has a photograph of two young Indian princesses smiling demurely in their saris, while the other students are dressed in school uniform. Princess Rajendra Kumari and Manher Kumari, nieces of Maharaja Ranjitsinhji Bahadur of Nawanagar, were sent to study there in the 1930s. They were permitted to wear saris and are said to have worn a new one every day.

In 2010, the school closed down after the last batch completed its schooling—there weren’t enough students. The nuns continue to live at Kylemore. They administer the estate, creating handcrafted products and gardening. The 6-acre Victorian Walled Garden designed by the Italian experts hired by Henry has been restored by the nuns; it has, in fact, won many awards.

At first, the walled garden seems to be like any other well-manicured garden: serpentine flower beds, fern paths, neatly trimmed hedges. But what captures my imagination are the 21 glasshouses set up by Henry in the 1860s. Two of them, restored by the nuns, are used to grow exotic fruits and vegetables, just as the Henrys did earlier.

I get to taste these vegetables at the Mitchell Café, where hot meals and desserts are made from recipes passed down by the nuns, using ingredients from the garden. I only have time for a quick bite before the tour bus takes off to its next destination. As I dig into the hearty vegetable soup, bursting with the flavours of fresh herbs, I wonder if this Taj of Ireland has found its “happily ever after" in the hands of the Benedictine nuns.

Trip planner

Go

Indian metros have flights to Dublin. From there, take a bus or train, which can cost ₹ 6,000 or more, to Connemara, 190 miles (around 300km) and five-and-a-half hours away.

Stay

Galway, which is a couple of hours’ drive from Connemara, offers many hotels in varying budgets.

Eat

The estate has two restaurants on site. The Tea House by the walled garden offers tea and snacks and the Mitchell Café, full meals.

Unlock a world of Benefits! From insightful newsletters to real-time stock tracking, breaking news and a personalized newsfeed – it's all here, just a click away! Login Now!