Jerusalem of the East

A walk through the Maghen David Synagogue and other landmarks of the city's Jewish quarter

Premium

Premium

It’s early morning and Brabourne Road smells of oranges and spicy omelettes. Karim Khan turns the eggs around in his battered charcoal-black pan and deftly drops a slice of bread in. As the quintessential Bengali street food deem pauruti takes shape, we casually point to the spire of a red and yellow building across the road. He promptly responds, “Ota toh yehudi der girja (It’s a church for Jews)."

The Maghen David Synagogue is no newcomer to the world of paradoxes. It stands quietly at the junction between Biplabi Rash Behari Bose Road and Brabourne Road, in that old weird Calcutta where magic and menace share the same dusty pavement. The latter got its name from Lord Brabourne, governor of colonial Bengal. Rash Behari Bose was a revolutionary who fought for independence. The 132-year-old synagogue stands right at the intersection of such contested history.

It reposes in lazy indolence, like the decadent royals of yore. The brown dirt has been paved over many times; the palanquins and parasols have given way to metal monsters on wheels, belching noisy fumes. It is a startling contrast to the landscape aquatint by Scotsman James Baillie Fraser (Plate No.17, from Views Of Calcutta And Its Environs, 1826). In it, you see the cows, the heavy, grey air, bursting with heat and blurred lines, and the Igreja Portuguesa, or The Cathedral of the Most Holy Rosary. The cathedral is the only element that has withstood the test of time.

The Kolkata of that era was divided, like a fallen empire or a country pie, into three unofficial zones—the White Town where the Europeans lived, the Black Town for the natives, and the tumbledown Grey Town, which was home to Armenian, Greek and Chinese immigrants as well as the Baghdadi Jews.

The history of Jews in Kolkata is remarkable. Most of them are called Baghdadi Jews, since they made their way from Iraq and Syria. The first recorded Jewish immigrant here was Shalom Aaron Obadiah Cohen, a gem trader from Aleppo (in Syria) who arrived in 1798 from Surat. Folklore has it that he had been asked by maharaja Ranjit Singh, the then ruler of the Punjab, to evaluate the Kohinoor diamond. Shockingly, Shalom Cohen found the diamond to be of no value and felt it could only be gifted or taken through bloodshed. His words were prophetic—Duleep Singh, Ranjit Singh’s son, had to hand over the gem to the British East India Company after the Second Anglo-Sikh War.

The Baghdadi Jews slowly made the city their home, but lacked their own place of worship. This prompted the construction of the Neveh Shalome in 1831, by Shalom Cohen himself. Austere and elegant, the temple’s whitewashed walls and muted splashes of green gave birth to Jewish religious life in the city. But the community kept growing in size, and another synagogue was commissioned.

The early Jewish community’s religious practices and food habits had much in common with Muslims. The rules of kashrut—Jewish dietary law—meant most Jewish households ate beef and stayed away from pork. This kept potential Hindu domestic workers at bay, while Muslim workers found it easier to work in their kitchens. Trading in Burrabazar and Chitpur was mostly the domain of the minority communities—the Armenians, Portuguese, British, Dutch and Jews. Segregated by colour, the three zones of the city had semi-permeable membranes, letting in coin and cart, but prohibiting social integration.

These zones have since disappeared but their memory lingers on in the names of the streets—Synagogue Street, Old China Bazar Street, Portuguese Church Street, Armenian Street, Ezra Street.

The approach to Maghen David is masked by an array of shops, some of which have started nudging at its green iron gates. As we wait for the gates to open, yet another paradox greets us in the shape of Rabbul Khan, the synagogue’s caretaker.

A Sunni Muslim, he ensures we follow the Judaic rules of entering a holy site. He puts on the kippah, the Jewish skullcap, before swinging open the heavy wooden doors to the prayer hall with visible pride. We are immediately drenched in visual decadence—blue, yellow and red stained-glass panels and windows envelop our senses, as do the brilliant antique chandeliers. We walk in the shimmering shadows cast by the stained glass on the chequered marble floor, admiring the floral granite columns. Rabbul takes us around and, explains, in meticulous detail, the ceremonies performed there. He remembers the last Jewish wedding that took place, in 1980.

On the same campus as Maghen David, the slightly elevated entrance to Neveh Shalome is accessible through a rickety old wooden plank that masquerades as a fire escape. Sheikh Masood Hussein, caretaker and general guide-at-arms, greets us. The youngest caretaker of all the main synagogues, Hussein is a graduate from Gop College in Odisha’s Puri—the most educated of them. We learn that all the caretakers are from villages in Puri district’s Kakatpur block. The three generations of Sunni Muslim caretakers of the city’s three synagogues hail from the same part of town. “Destiny, perhaps!" muses Hussein.

In West Asia, Sunni Muslims and Jews have been engaged in one of the longest-standing conflicts in modern history. In faraway Kolkata, they look after each other. In the Old City in Jerusalem, two Muslim families have been entrusted with the key to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for centuries. Perhaps Kolkata simply mirrors that.

Will this last? Rabbul, Anwar and Hussein are perhaps the last of their kind, much like the remaining 20-odd Jews in Kolkata. It doesn’t pay to be a caretaker, and their children are not interested in carrying forward the family tradition. The caretakers get a free residence inside the campus, but even that is crumbling into disrepair. Yet Anwar hangs photos of himself with eminent visitors on the plaster-peeled walls of his narrow room, damp on the ceiling and the tropical rain forever threatening ingress. The shrinking of Kolkata’s Jewish community has set alarms bells ringing, and the uncertainty about the preservation of Jewish heritage looms large not only for the remaining Jews but also the caretakers.

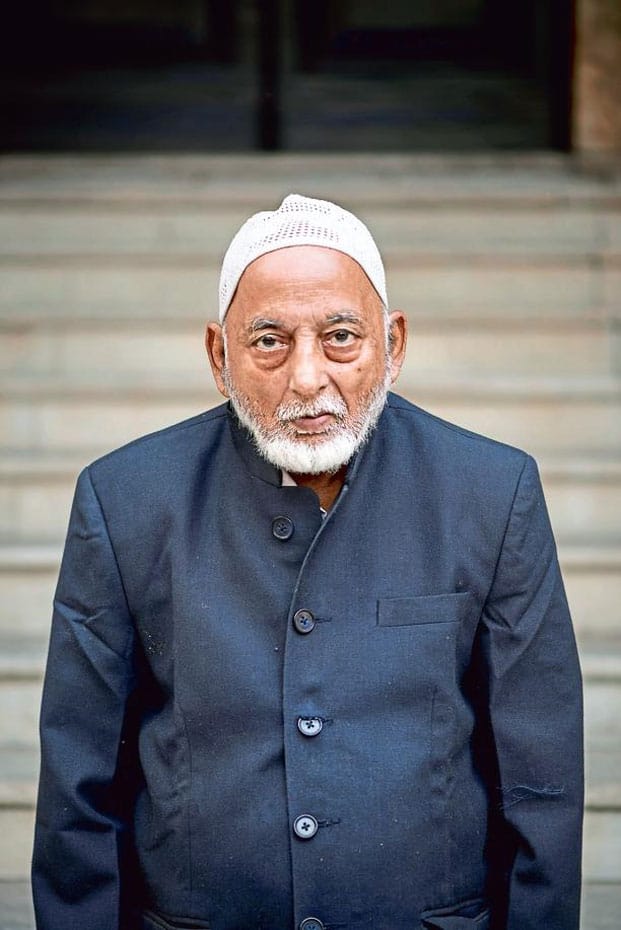

We stop at the Beth El Synagogue on Pollock Street and meet Siraj Khan, a third-generation caretaker. “It’s a good thing in Islam to support someone who is trying to honour his religion. We do it as an act of faith. Even though there are so few of them, they are still committed to saving their way of life." As we leave, we meet Khalil Khan, Siraj’s father, who served for many years as the caretaker of Beth El, and has retired recently. His beard is as white as his crocheted taqiyah (skull cap), and his eyes trickle a certain sadness.

We return to the din and dust of Fraser’s intersection at Murgihata, overrun with shops selling tea, paint and iron trunks. This is where the friendly footsteps of three different faiths decussate delicately.

Connect the Neveh Shalome with the Portuguese Church to its left, and the Canning Street Masjid to the right, and a mystical obtuse triangle emerges. These are Calcutta’s very own ley lines, the old city aligning with the new, where the star, the crescent and the cross merge into a toe dance of hope and urban decay.

Unlock a world of Benefits! From insightful newsletters to real-time stock tracking, breaking news and a personalized newsfeed – it's all here, just a click away! Login Now!