What is behind inter-state differences in inflation?

Considerable differences persist across states in terms of retail inflation, mostly on account of rural food price rise

Premium

Premium

Mumbai: With consumer price inflation fast emerging as the focal point of monetary policymaking in India, perhaps it is time to delve into the not-so-insignificant differences in inflation across states.

To begin with, inflation, both retail and wholesale, has risen in recent months. This has raised concerns about the scope of further interest rate cuts in the near future.

All-India retail inflation is now at a 23-month high of 6.07% year on year, above the upper bound of the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) inflation target.

However there are five major states—Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand—with inflation below 5% in July 2016; that is, below the target set by RBI for March 2017.

On the other hand, inflation is now more than 6% in 11 of the 23 major states and Union territories (including Goa and Delhi).

Therefore, it might be useful to know what is causing the differences across states.

Data from the ministry of statistics and programme implementation (MOSPI) shows that the inter-state variation in inflation is mostly a rural phenomenon, with much of it being driven by differences in rural food inflation.

The current series of consumer price inflation, with year 2012 as the base, consistently shows the inter-state variation, or standard deviation in rural inflation, to be higher than in urban inflation.

Not only does rural inflation vary more across states, it is also generally higher than its urban counterpart in each state. Moreover, states with higher overall inflation also tend to exhibit a wider rural to urban inflation gap, with rural inflation exceeding urban inflation. To illustrate, a scatter plot of overall inflation for different states against their ratio of rural to urban inflation reveals a positive correlation.

To elaborate, the difference between rural and urban inflation is much wider in states with relatively higher inflation, namely, Odisha and Gujarat, compared with states that have relatively lower inflation, namely Assam and Himachal Pradesh.

Also, in case of states with relatively higher inflation, it is mostly rural food inflation that is driving the rural-urban gap in those states.

Rural food inflation exceeded urban food inflation in the four major states which witnessed the highest overall inflation in July 2016. It means that rural inflation would have still exceeded urban inflation in these four states even if the rural consumer price inflation basket had the same weight assigned to food as its urban counterpart.

The divergence in zone-wise rural food inflation in India is now the widest since at least January 2014, when measured by the absolute difference in inflation between the maximum and minimum food inflation across the six zones.

Currently, rural food inflation in the western zone (Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa and other Union territories) is estimated to be around 11.3% year-on-year, compared to an estimated 3.9% year-on-year rural food inflation in the north-east.

Within food prices, it was mainly pulse and vegetable prices which led the rise in prices. While pulse prices rose in almost all states, what differentiated the low-inflation states from the high-inflation states was the inflation in non-pulse food items. In many of the non-pulse food items, the low-inflation states fared much better; that is, showed a slower price increase.

Thus, the inter-state differences in inflation appear to be attributable to differences in rural inflation, which in turn is largely on account of differences in rural food price inflation. Now the question arises is, what is causing variation in food prices across states?

“The variation in inflation across states could be partially attributable to inter-state transportation costs and to the differences in tax regimes across states, which often impede equalization of prices across regions," said Rajeswari Sengupta, professor of economics at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research in Mumbai.

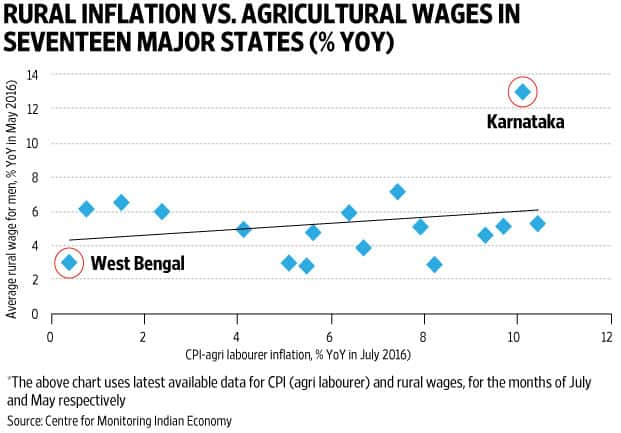

Do state-wise differences in rural wages explain the differences in inflation?

Prima facie, there exists only a weak positive correlation between the state-wise rise in rural wages and states’ rural inflation, as measured by the consumer price index for agricultural labourers, with base year as 1983.

Correlation does not necessarily imply causation. Moreover, the correlation gets weaker if we use the rural consumer price inflation according to the new series, that is with base year as 2012. The possible impact of rural job guarantee, that is the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) on rural inflation, by raising rural wages and hence cost of farm inputs, has been a matter of much debate.

However, MGNREGS may not have been the only factor pushing up rural wages, as noted by a 2012 RBI occasional paper authored by G.V. Nadhanael. According to the paper, the rise in rural wages post-2007 can be attributed to a shift in labour supply from agricultural to non-agricultural work, like construction and services segment.

Meanwhile, the drop in labour force participation rates of women also contributed to the rise in rural wages.

Such a rise in rural wages could be one of the factors responsible for higher inflation as “wages impact prices… (by) …feeding into cost of production" as argued by the RBI occasional paper. However, the causality might often run in the other direction, as noted by the paper itself, when nominal wages adjusted to rise in prices. Thus, it is as yet difficult to say whether or not rural wages are the driving force behind rural inflation. If not, then we would have to search somewhere else to find clues on what is causing differences in rural inflation across states.

Given the not-so-insignificant variation in inflation across states, further attention and research is required on the subject.

Unlock a world of Benefits! From insightful newsletters to real-time stock tracking, breaking news and a personalized newsfeed – it's all here, just a click away! Login Now!