Why don’t we have rainbow-coloured people?

Any which way you look at it, the big five tech companies have taken over our lives. Each of us live in a monochromatic world they dictate. Do we have to?

Premium

Premium

The last week was a very interesting one. Much debate in India around privacy transpired. It continues. A lot of sound and fury has followed since the Supreme Court ruled it is a fundamental right under the Constitution of India. Many people are tracking the implications of it all with much interest. Even as this verdict was delivered and the debate is on, war on another turf has permeated our lives in insidious ways. Technology companies want a slice of us. And the rules by which they are playing seem beyond our comprehension.

Some perspective is needed here. Every news report has it that phone tariffs in India are among the lowest in the world—if not the lowest already. If we are to go by publicly available World Bank data, on average, it costs $2.80 (as computed in 2014) to operate a cellular phone. We know the latest numbers are lower on the back of competition and exchange rates. But because I thought this the most credible and authenticated set of data I stumbled upon, allow me stay with this number for the moment. When converted into Indian rupees, at current exchange rates, it works out to just about Rs180 a month.

Turns out, two kinds of people exist in India in the post-paid telecom market.

1. Doofuses like me who pay in the region of Rs3,000 or more each month on the back of plans they had subscribed to at some point in time and haven’t bothered to check the fine print since then.

2. The prudent ones who pay anything in the region of Rs500-1,000—inclusive of taxes.

Whatever am I burning my money for, I wondered. It was inevitable then that calls start going out of from my phone to rival carriers even as I dialled the incumbent operator whose network plan I was on. Overnight, the table turned.

Everyone started to bid to have me on their network. All kinds of sops were thrown in. I didn’t know until then that unlimited talk time with free national roaming facilities is now a norm and not an exception. What got me by surprise, though, was the ferocity with which every carrier tried to outdo each other to woo me with high-speed data plans. I was being spoilt rotten. Not just that, costs were slashed to less than a third of what I was originally paying for. Incidentally, these plans are not advertised. Details are shared only when haggled for over the phone much like you would with a vendor at a regular bazaar.

When and how did this battle to acquire insignificant people like me gain such ferocious momentum? Huge entities like telecom operators are bankrolled and valued in the billions of dollars. Why do they want you and me so bad? In fact, if one were to sit down and do the math on the back of the tariffs on offer, from an operator’s perspective, the numbers don’t make sense. It looks bleak and folks like us would baulk at the thought of doing business in a regime like this.

But apparently, companies want to retain creatures like us. They are willing to not just do it, but bludgeon their balance sheets with even more blood than what is apparently already on it. On the face of it, it sounds stupid. But let’s get this right. There are some mighty smart entrepreneurs running these places. What are they thinking? The numbers tell a tale.

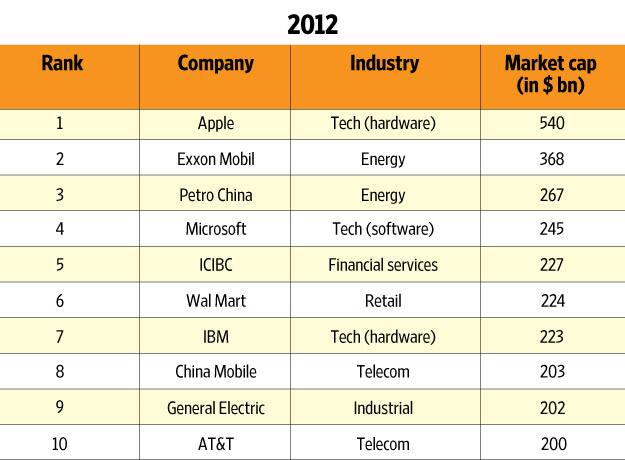

The first table shows the world’s largest companies by market capitalization in 2012.

But that was 2012. And five years is a long time. Seven of the top 10 companies in the world are now embedded in technology. The lone energy company has not just slipped down the ladder, but has lost out on market capitalization as well, while others have slipped out of sight to make way for a new world order. The state of affairs in 2017:

When thought about, what this means is that for all practical purposes, technology companies driven by data have now colonized the world. This has been in the works for a while, has been well documented, and was anticipated for a while now.

What is not documented and taken as seriously though is that they now control how you and I think. What has changed from 2012 is that is our world is not just gotten flatter—but smaller as well. Our brains are perhaps shrinking as well. So, what is really going?

The irony of it all is impossible to miss. As early as March last year, I had argued why platforms like Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn are snarky ones. My limited submission then was that the earlier you get out of platforms like these, the better off you are. Facebook amplifies biases, the environment on Twitter is abusive and LinkedIn violates privacy (as do the others).

What I hadn’t put on the list then is the nature of the beasts that are Google and Apple. My paranoia insisted I get off all these places. But as things are, and as I have confessed in the past, I am back on all platforms, except LinkedIn. Not for anything else, but because I’m trapped. All of us are trapped.

Some pointers as to why are we “trapped" come from Eli Pariser. He documents it all in his best-selling book around a phenomenon called the “filter bubble", a theme on which he has delivered multiple talks as well.

Very simply put, Pariser’s studies clearly suggest that if you and I are to post a query on Google, the results that emerge will be very different for each of us.

For that matter, the feeds you see on Facebook will be different as well.

Why? Because, Pariser explains, the algorithms that power these companies are doing their best to create “a unique universe of algorithms for each of us… This fundamentally alters the way we encounter ideas and information".

Again, it is pertinent that we ask why. When you visit any platform that promises to offer a personalized experience, among the first things we are asked to do is to sign up. And to do that, we part with information. This includes what sounds trivial like our names, age, location and gender, among other things. Over time though, this information is extrapolated against the places we visit, what we do on the sites we visit and how we behave there, via pieces of software called cookies. These keep track of every move we make and capture data. Eventually, it gets to know us better as individuals than our mothers or spouses imagine they do.

Again, why should this matter?

Because we are a function of what we see and the people we interact with.

To get the import of that, step outside the digital world for a moment and look around where do you live. What do you see around? Whom do you talk to? Where do you work? What are your interests? What gets your attention? What is your preferred mode of commute? What and whom are you emotionally attached to? All of this come together to weave a network that is our world and shapes our world views.

In the offline world, we are molded by the voices of those whom we choose to surround ourselves with. Why should this be any different in the online world. To that extent, as Pariser observes, “Your computer monitor is a kind of one-way mirror, reflecting your own interests while algorithmic observers watch what you click."

Now, what do they do after having watched us as closely?

Pariser has some pointers.

“… The top fifty internet sites, from CNN to Yahoo to MSN, install an average of 64 data-laden cookies and personal tracking beacons each. Search for a word like “depression" on Dictionary. com, and the site installs up to 223 tracking cookies and beacons on your computer so that other Web sites can target you with antidepressants. Share an article about cooking on ABC News, and you may be chased around the Web by ads for Teflon-coated pots. Open—even for an instant—a page listing signs that your spouse may be cheating and prepare to be haunted with DNA paternity-test ads."

If that isn’t enough, consider this.

“When you read books on your Kindle, the data about which phrases you highlight, which pages you turn, and whether you read straight through or skip around are all fed back into Amazon’s servers and can be used to indicate what books you might like next. When you log in after a day reading Kindle e-books at the beach, Amazon can subtly customize its site to appeal to what you’ve read: If you’ve spent a lot of time with the latest James Patterson, but only glanced at that new diet guide, you might see more commercial thrillers and fewer health books."

All of this is not new. Pariser’s findings have been in the public domain for a while now. In fact, that is one among the many reasons why early on in this series of dispatches, I had urged we turn instead to engines like DuckDuckGo and away from platforms like Facebook. But I capitulated. Why did that happen?

As recently as last week, a Canadian news channel reported concerns around what is going on. By way of example, the author writes, “What ‘the big five’ are selling—or not selling, as in the case of free services like Google or Facebook—is access. As we use their platforms, the corporate giants are collecting information about every aspect of our lives, our behaviour and our decision-making. All that data gives them tremendous power. And that power begets more power, and more profit."

“On one hand, the data can be used to make their tools and services better, which is good for consumers. These companies are able to learn what we want based on the way we use their products, and can adjust them in response to those needs."

“It enables certain companies with orders of magnitude more surveillance capacity than rivals to develop a 360-degree view of the strengths and vulnerabilities of their suppliers, competitors and customers,"

“Access to such sweeping amounts of data also allows these giants to spot trends early and move on them, which sometimes involves buying up a smaller company before it can become a competitive threat… Buying up a smaller company before it can become a competitive threat."

What it means is that while Duckduckgo may have its heart in the right place, the search engine is an exasperating one to work with. It does not have enough muscle in it yet to index as much information as Google can. The latter has grown so big and can do as much as it can now because it controls 81% of the market for search. The closest competitor it has is Microsoft’s Bing—which, with all the resources at its disposal, attracts just about 7% of the world’s population who go online. Duckduckgo does not fit into anybody’s scheme of things.

In much the same way, there is no escaping Facebook. Two billion people are on it. What chance does any social networking site stand against the might of these kind of numbers? These are the kind of numbers that make Google and Facebook larger than India or China, the world’s most populated nations.

When looked at from a business perspective, Standard Oil, the world’s largest oil refinery at its peak in the 1890s, commanded 79% of the global market share before anti-trust authorities felt compelled to step in to control the monopoly. They thought at the time that the entity was a danger to the sovereign. In that sense, the big five tech companies are bigger, and perhaps more powerful than nations like India, China or the US.

So, if data is being offered on tap and seemingly at throwaway prices, it is an illusion. It is the new currency that the nations of Facebook or Google need to lubricate their economies. And they do it via innovative business models that use the networks built by telecom operators. These operators have no choice, but to capitulate and work at creating models that appease the demands placed by these “nation-states".

In other words, “free data" is the currency to swap “free will". Essentially, by accepting it, we sign off on that we are comfortable living in a filter bubble that entities like these create.

Is this desirable? Whoever would have imagined a day like this would come? Can we now think of a world without Google or Facebook?

Do the answers lie in looking at countering technology with more technology?

Let’s be pragmatic about this. We’re talking about seriously powerful entities. Whether they are evil or not is a matter of perspective. As things are, may I submit that taking on technology with more technology is pointless. On the contrary, it adds to the noise.

What are we to do? Some pointers emerged from an engaging online conversation with Rahul Matthan, that was anchored by my colleague N. Ramnath and me on the “future of privacy". Matthan is a partner at Trilegal and columnist for Mint.

His answers, while embedded in law, also suggests that we understand and be aware that we are human. For instance, on the ferocity of arguments over who is right and who is wrong, his take was a simple one. “We live in an age of incredible closeness. Technology has made it such that we can watch what is happening in Houston (down to Melania’s high heels) just as Houston can see what is happening in Mumbai. So, the discussions are much more ferocious than it ever was…"

Is it possible to regulate then?

“It is actually very hard to regulate in these environments. Because—let’s face it—there is no right answer to these questions. We can suggest solutions."

Then, as Matthan puts it, once upon a time, “we assumed that machines, being unmotivated by human emotion, are incapable of bias. But we are now beginning to realize this is not true. It has the same biases we have. And some more. It is this realization that has forced us to re-think the trust we have reposed in machine-based decision making… But with machines, the consequences can be greater because given the scale at which these decisions are made, the biases are often hard to detect".

How are we to get out of our biases? The answer came the other night from the most unlikeliest of sources—my five-and-a-half year old daughter, who insisted I tell her a story so that she may go to sleep. Just when I was trying to think something up, we got into an interesting conversation.

“Dada, why does the world have only Indians, Americans, Africans and Chinese people?"

Her world, you see, is a simple one. Brown people are Indian, whites are American, black people are African and everybody else is Chinese. Even as I was trying to rack my head to think up an answer that may drive the nuances, she threw yet another one at me.

“Dada, why cannot everybody and everything be rainbow-coloured?"

Eh?

“Because see, that way, we can mix and match. Everybody and everything will look pretty and nice. And all will be well."

Clearly, I must step out with her more often and see the world from her eyes as opposed to mine, which are glued to the screen more than any other place. It makes my world a monochromatic one as opposed to her innocent view that can experience beauty for what it is and articulate it in as many words.

Charles Assisi is co-founder and director, Founding Fuel.

His Twitter handle is @c_assisi

Comments are welcome@feedback@livemint.com

Unlock a world of Benefits! From insightful newsletters to real-time stock tracking, breaking news and a personalized newsfeed – it's all here, just a click away! Login Now!